Image credits: Jones

This news was originally published on the Durham University website on 11 August 2022.

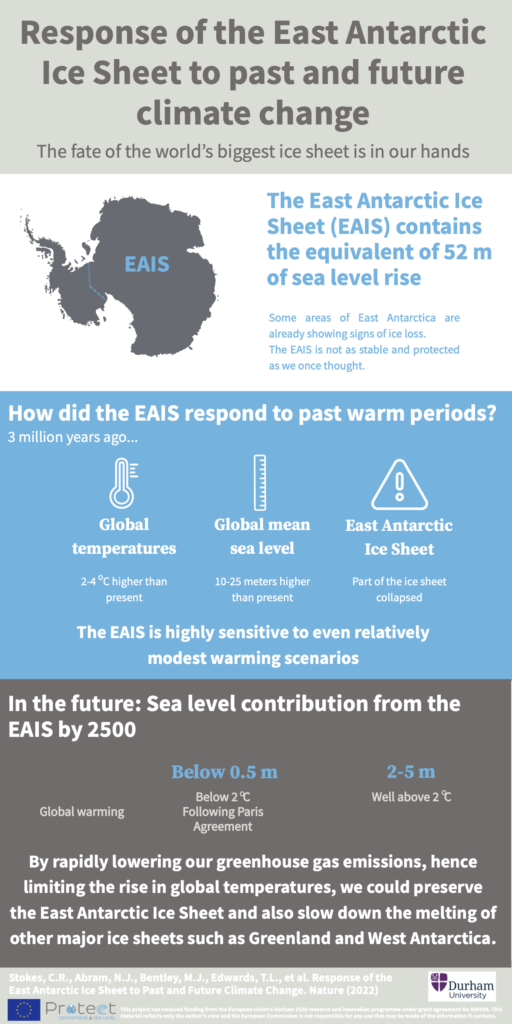

The fate of the world’s biggest ice sheet is in our hands, researchers say.

A new study led by the Geography department of Durham University shows that the worst effects of global warming on the East Antarctic Ice Sheet (EAIS) could be avoided.

That depends upon temperatures not rising by more than 2°C above pre-industrial levels – the upper limit set by world leaders in 2015 under the Paris Agreement on climate change.

Staying below this limit would see the EAIS – which holds the vast majority of Earth’s glacier ice – contribute less than half a metre to sea level rise by the year 2500.

But continued warming beyond the 2°C limit could potentially see the EAIS contribute up to five metres to sea-level rise in just a few centuries.

Greenhouse gas emissions

Researchers looked at how the ice sheet had responded to past warm periods, as well as examining where changes are currently happening.

They then analysed a number of computer simulations from previous studies to examine the effects of different greenhouse gas emission levels and temperatures on the EAIS by the years 2100, 2300 and 2500.

If emissions are dramatically cut and there is only a small rise in temperature, the ice sheet might be expected to contribute around two centimetres to sea level rise by 2100 – much less than the ice loss expected from Greenland and West Antarctica.

If the world continues on a pathway of very high greenhouse gas emissions, there is a possibility of the EAIS contributing nearly half a metre to sea levels by 2100, but the researchers viewed this as very unlikely

And if emissions remain high beyond 2100, the EAIS could contribute around one to three metres to global sea levels by 2300, and two to five metres by 2500.

This would add to the substantial contributions from Greenland and West Antarctica and threaten millions of people worldwide who live in coastal areas.

Past warming

The researchers also reviewed how the EAIS responded to past warm periods, when carbon dioxide concentrations and atmospheric temperatures were only a little higher than now.

Unlike the very rapid and extreme warming that we’ve experienced over the last few decades – that can only be explained by greenhouse gas emissions from human activity – past warming happened over much longer timescales, and was largely caused by changes in the way the Earth orbits the Sun.

A key lesson from the past is that the EAIS is highly sensitive to even relatively modest warming and is not as stable and protected as once thought.

As recently as 400,000 years ago – not long ago on geological timescales – there is evidence that part of the EAIS retreated 700km inland in response to only 1-2°C of global warming.

Restricting global temperature increases

World leaders agreed to limit global warming to well below 2°C and pursue efforts to limit the rise to 1.5°C under the Paris Agreement.

According to the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, human activity has increased global mean temperatures by about 1.1°C since pre-industrial times.

Research lead Professor Chris Stokes said: “A key conclusion from our analysis is that the fate of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet remains very much in our hands.

“Restricting global temperature increases to below the 2°C limit set by the Paris Agreement should mean that we avoid the worst-case scenarios, or perhaps even halt the melting of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, and therefore limit its impact on global sea level rise.”

Image and video credits: Richard Jones and The Lewis Pugh Foundation/Steve Peters/ Michael Booth

The results at a glance

Find out more

- Read the research paper in the journal Nature.

- The research was led by Professor Chris Stokes, Department of Geography, Durham University. Watch Chris explain the research.

- It also included experts from King’s College London, and Imperial College London (UK); the Australian National University, University of New South Wales, University of Tasmania and Monash University (Australia); Université Grenoble Alpes (France); the University of Colorado Boulder, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and Columbia University (USA).

- The research was funded by the UK Natural Environment Research Council; the Australian Research Council Special Research Initiatives in the Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science, and Securing Antarctica’s Environmental Future; the Centre for Southern Hemisphere Oceans Research; the Australian Antarctic Program Partnership; the European Union’s Horizon 2020research and innovation programme; and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

Leave a Reply